In Mina Khan’s debut poetry collection Night Shift in Perfect English, individual memories are rendered in such a way that they become collective hauntings. The cycles of time, death, and desire are specific to the author’s subjectivity––that of a Korean-Pakistani daughter in New York, caught between her family apartment and the bodega owned by her parents. Yet these specifics are also transformed into openings that the reader can walk through, as Khan beautifully uses lineation, white space, imagery, and multilingualism to invite the audience to remember the commonality of pain and hope, how they persist for all beings. I had the opportunity to talk to the writer about these themes, the scale of time, want, and more.

Sarah Yanni (SY): You wrote a book.

Mina Khan (MK): I wrote a book.

SY: You have these tremendous blurbs on the back of your book, and I think something we all observed is how your collection has a lot to do with cyclicality and return. The last poem in the collection is called life as pendulum, and I just keep coming back to that title––it felt very central to the movement of the collection.

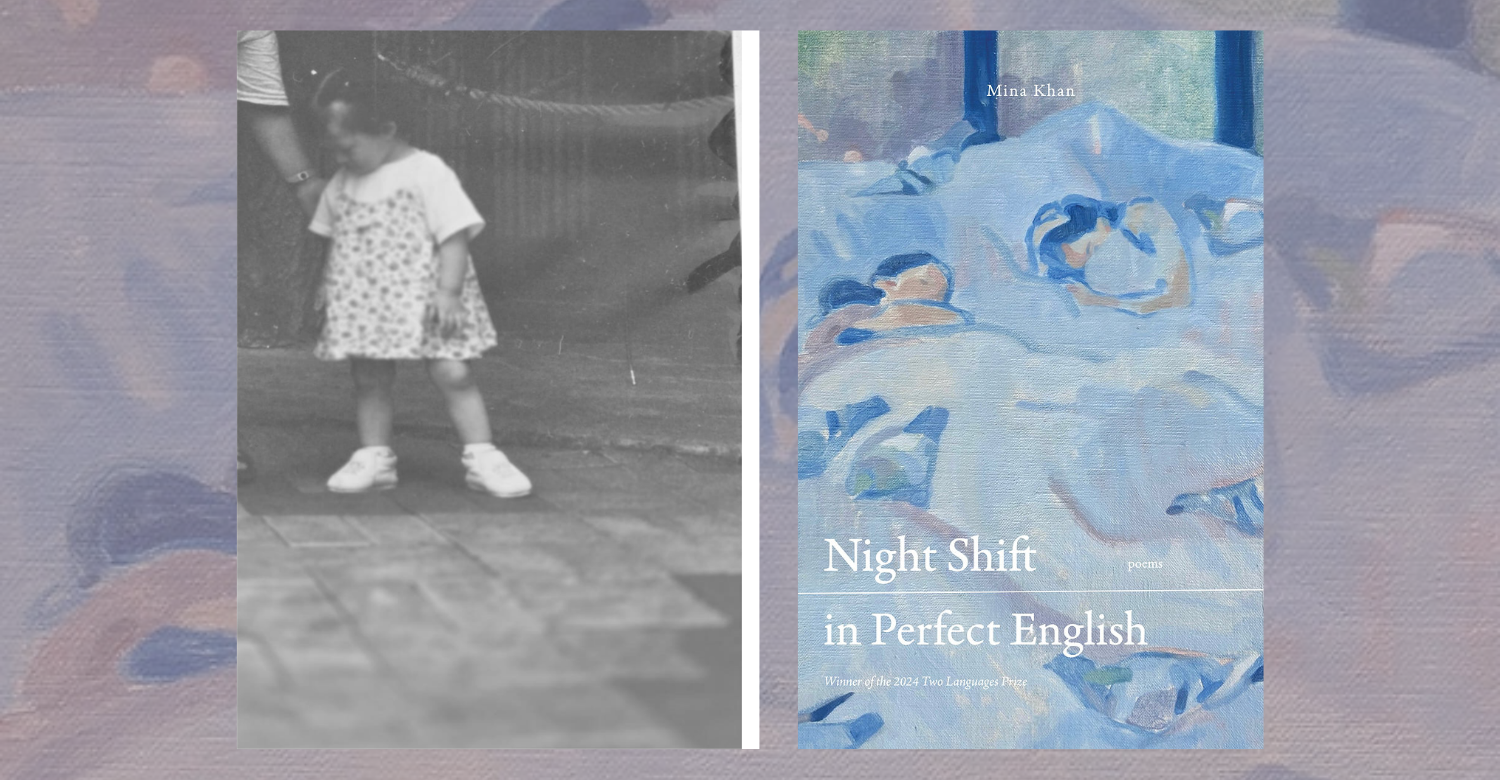

In Diana Khoi Nguyen’s blurb, she calls attention to the different mediums you’re working in––she mentions the use of the screenplay format, as well as images. And of course, Diana uses images in her work so much, with a very literal relationship to the ghostly or to haunting, because of the way she features the cut-out images of her deceased brother in Ghost Of. And while you’re not manipulating images in that exact same way, there is still something very ghostly about your use of them. So I wanted to start with your thoughts on the use of different forms and mediums––how or when did that come into the process of putting together this collection? Why did you choose to include images and the screenplay format?

MK: Yeah those blurbs are an honor. I’m so grateful. And I guess form to me is connected to my obsession with memory, which is what is central to my writing. I know that I speak very specifically about my own familial experience, but I want it to feel collective. And I try to use repetition in my work in a way that the reader might be like, “I’ve heard this before…it reminds me of something…it’s on the tip of my tongue…” and I think that’s what I was trying to conjure by using images. It’s almost this experience of time distorting memory, and thereby distorting the images. And then the book is in non-chronological order, and so I wanted to include the screenplay format because it’s a way that the reader can situate themselves physically and emotionally.

SY: It’s almost like you’re trying to conjure this sense of déjà vu for the reader.

MK: Exactly!

SY: And the “scenes” being set in the screenplay format start as quite physical but then they are more about a feeling.

MK: Yeah, it’s more of a return to this recurring emotion of dullness, and also pain.

SY: Your epigraph is from Louise Glück––“We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.” And the way I interpreted that was almost like: to be an adult is to be an unreliable narrator. So maybe we’re all just unreliable narrators, and what do we do with that? What’s your relationship to Glück’s work?

MK: So this book was written from 2020-2025, and she was someone that was really important for me in the latter half of that. I love the way she talks about nature and speaks so intimately about details, and the relationships between people through the most minor thing, like a hand on a chair. I wish I could say more about how she’s influenced me, but she’s just good. Like, when I read her I want to write.

SY: No totally, I love finding those writers that just activate you. The ones that remind you why you want to write poetry in the first place.

MK: And I think that epigraph is a pretty popular quote of hers, but I do think it speaks directly to the themes of my work, my obsession with memory and childhood, especially familial history. I feel like that quote says that we kind of fictionalize our lives, continuously, because we’re not seeing them anymore. Everything is just pieces of the past that we’re trying to put together.

SY: Yeah there’s a line in your book that I wrote down actually, from the poem everything returns to itself, “everything is true if you say it, / really feel it.”

MK: Yeah, exactly – we remember through distortions, and then those distortions are our truths, our realities.

SY: And how do we make sense from that place? There are certain patterns or tensions through which you make meaning that I noticed repeating themselves in your book. The first is this constant coexistence of pain and pleasure. You have a poem where you explicitly name that duality, mentioning things like “aliveness” and then “credit card debt.” And of course, there is literal death and life at play in your works. You’re operating across these really distinct scales. And then I started going in a thought spiral about how maybe that coexistence of pain and pleasure is inherent to the diasporic condition… Another pattern is just the presence of pairings, between the apartment and the bodega, between your two cultural backgrounds…and I guess my question is: are these poems interested in wholeness? Is that an aspiration?

MK: I do see all of life as a push and pull of pain and pleasure, especially being an immigrant daughter. That does exist in being mixed, and that does exist in diaspora. But I also think that it is inherent to a being a thing that’s alive. We’re all living within the post-American Dream world, we’re all in late capitalist America under certain forms of duress, climate change, you know. We hurt each other, and we’re being hurt. And we’re trying to survive but we are immensely cruel to one another, without even meaning to be sometimes. Like I step on a bug, that bug is dead. And I think we’re so disgusted with things trying to survive. How we hate animals for being here, in these cities that are incompatible with them. So I think it’s less about wholeness and more about the inevitability of our participation in these cycles of violence. That’s what I wanted to think through.

SY: We’re conscripted into it. You have a middle section in the book, with the repeated title the neighborhood is changing. And in some ways, it seems like the book is about how so much is changing, but it’s also a book about how so much stays the same. And I think migration creates its own mythologies around time, maybe working at larger scales across generations or lifetimes rather than being attached to dailiness.

MK: Yeah, it’s bigger than that day-to-day, and there’s so much mythologizing that comes with the pre-migration, the actual migration, post-migration, so on. I think about my mother a lot, the whole mythology of her having to move away from Korea, which was one of the most impoverished countries in the world at the time––she was starving––and the hope she saw in coming to the U.S. And now, to only be in a marginally better position than she was back then, with the country she left now being a home of so much uber wealth and economic gain. I guess that’s something that haunts me, how time turns over and you think so much has passed, but so much is still the same.

SY: It’s a circle, and then it’s a circle that like, hits a thick wall. Your mother feels really important in this collection, not just as a character but as someone you’re really psychically tied to––you talk about how you both stop stories in the middle, how you have a shared syntax. And I noticed in a lot of your pieces you play with sparseness and white space. There’s something about that stop and start, that play with absence, that reflects that halted speech you both enact. And it also mirrors the inability to progress fluidly in the way that the American Dream would have promised.

MK: Absolutely. I also think about language barriers a lot when it comes to my family. And the capacity to discuss emotion, how that’s lost across second or third languages. On top of that, my parents––like many older people––weren’t taught to talk about their feelings in general. And so in a way, I feel like I’m never fully connecting with them. There’s so much jumping and translating. There’s so much I’m never going to understand. Sometimes I do wonder if my mother is trying to connect with me in a way that I just don’t get. And I want it so badly.

SY: Want is also something I wanted to ask you about. One of the things I really loved about this collection is that the narrator isn’t just an observer or chronicler of events. There is a persistence of desire and selfhood that really came across for me. I wrote down this line from your poem what we have done that I really loved – “beside all goodness is more of the same–– dark hues / of repetition. engines bring clouds to concrete. / yet I am standing here / wanting more.” Despite everything, there’s still that sense of agency, and desire.

MK: You know, I think the feeling of wanting something is so powerful and so beautiful. I’m even thinking about bugs again, how we have these mutual desires––we both really want food, we both really want shelter, to be safe…and that drives us to continue going. Survival is want.

SY: Bugs and mosquitos and cicadas are repeated motifs for you. Was that on purpose? Did you write them as a series?

MK: No! When I was putting together my poems to see if I could actually make a collection, I saw that I just kept writing about mosquitos. So I was like, should I just make a chapbook about bugs and flowers? But I decided not to, and then it just coincidentally became this larger project.

SY: Is there anything else about the process of putting together the book that you’d like to share before we finish?

MK: I guess just to share some closing thoughts on intuitive lineation. I don’t follow a form, but it’s also not random. What I do is I start typing something, and I get into a rhythm, and the lineation is how I keep that rhythm. And for me, white space signals that something is not being said. And it’s also a space where the reader can transpose themselves into the work; it’s a physical space that allows that. Because these poems, to me, are like actors on the same stage being put into different scenes and configurations. And I want the reader to be brought through those scenes in a very real way. Because I don’t just write for myself. My experience is specific, sure, but it’s not singular––I think many can understand the experience of having the world and the people you love feel like they’re against you. And how still, you want more of it.

Sarah Yanni is a Mexican-Egyptian writer in California. Her work has been published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Mizna, Pleiades, Nat Brut, and Wildness Journal, among others, and has been recognized as a contest Finalist by BOMB Magazine, Hayden's Ferry Review, Poetry Online, Kelsey Street Press, and Letras Latinas. She is the author of two chapbooks--Hard Crush (Wonder Press, 2024) and ternura / tenderness (Bottlecap Press, 2019)--and has received support from Tin House, Community of Writers, the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, and The REEF. She holds an MFA from CalArts.

.png)